Curating Online Video Repositories for Teaching Sociology: A Digital Resource Discovery, Mapping, Retrieval Framework

Michael V. Miller & Anna CohenMiller

Abstract

This paper introduces a systematic framework for discovering, organizing, and retrieving video that can be employed to enhance sociology instruction. Rather than focusing on individual videos, we shift attention to Online Video Repositories (OVRs)—sites and channels that host aggregated collections for streaming. Drawing on internet search efforts that identified over 150 sociology-centered OVRs and numerous additional repositories from related disciplines, we demonstrate how instructors can efficiently navigate the expanding landscape of educational video through integrated digital curation technologies. Our approach combines RSS (Really Simple Syndication) feeds with social bookmarking to create a comprehensive curation framework. We developed visual RSS dashboards that automatically update as new content becomes available, providing real-time awareness of emerging resources across multiple repositories simultaneously. Complementing this discovery mechanism, we implement systematic social bookmarking, employing structured tagging taxonomies that enable precise retrieval based on subject matter, content type, production quality, and pedagogical applicability. The integrated system addresses current limitations in sociology's approach to digital media curation, where traditional individual-video identification methods cannot match the pace of content creation. By demonstrating how RSS and social bookmarking technologies can be combined to create sustainable, scalable curation practices, this framework offers instructors practical tools for systematically accessing and organizing the wealth of media resources now online.

Introduction

College instructors face a stark contrast to the multimedia scarcity of the early 2000s. Today, they have access to an overwhelming amount of potentially relevant content. Commercial websites continuously upload new material, while user-sharing platforms host an expanding array of professional and amateur productions—news reports, interviews, speeches, lectures, demonstrations, documentaries, film clips, and specialized instructional content. Indeed, the current rate of video creation has outpaced the capacity of academic disciplines that continue to employ traditional strategies to identify and describe content.

Despite this abundance, sociology as a discipline has been slow to develop systematic approaches for curating online multimedia. Publications in some fields like economics were quick to bring such resources to the attention of readers (see Sosin and Becker 2000), but those in sociology have essentially overlooked relevant production sites. As a result, even quality materials that could enhance instruction likely remain unknown to most teaching faculty. This limitation significantly constrains the integration of digital resources into sociology education—a challenge that became acute during the 2020 mass transition to remote teaching when instructors scrambled to find useful digital content (Fyfield, Henderson, and Phillips 2021, Nguyen 2022).

Such limited curation is also likely exacerbated by disciplinary expectations that inadvertently discourage efficient resource use. Unaware of existing quality film, instructors may feel compelled to expend scarce time creating video content. This misallocation of effort not only strains individual faculty but overlooks a critical fact: instructors generally lack the specialized video skills necessary to create content comparable to existing quality materials. Meanwhile, the prevailing academic emphasis on original content creation obscures the pedagogical expertise required for instructors to engage in effective curation—identifying quality resources, evaluating academic rigor, and integrating strategically into course design.

Pioneering efforts have emerged nonetheless to address this problem. Most notably, The Sociological Cinema broke important ground starting in 2010 by identifying and describing individual videos that could be used for teaching purposes. However, an individual-video approach, although still valuable for curating resources, cannot keep pace today with the rapidly expanding volume of relevant media. The current environment demands a framework that can efficiently identify, organize, and communicate the availability of sociological content at scale.

This paper shifts focus from individual-video curation to the systematic identification and organization of Online Video Repositories (OVRs). OVRs are sites and channels that host aggregated video collections for on-demand streaming. By prioritizing repositories rather than isolated videos, we offer a more efficient response to current curation challenges.

An OVR approach advances instructional capacity in two ways. First, it expands access to relevant content. When instructors find OVRs aligned with their teaching interests, they gain entry to entire collections of resources potentially applicable to their courses. This broader engagement can also foster the growth of creator-instructor networks essential for sustaining quality video production (Palmer and Schueths 2013). Discovering and using each other's video content creates opportunities for cross-institutional dialogue. Rather than instructors working in isolation to create similar content, such networks potentially enable a division of labor where instructors can focus their creative energies on their areas of greatest expertise while drawing upon the specialized knowledge of colleagues in other areas.

Our examination of OVRs represents the first comprehensive attempt to identify online video-creation sites relevant to teaching sociology. Building on an initial survey of open-access repositories across the social sciences (Miller and CohenMiller 2019), we have now added over 150 sociology-centered sites, most created by sociologists for their students. We have also cataloged even more repositories from related disciplines and non-academic sources that have sociological relevance. These resources collectively constitute a rich but previously undefined source of teaching materials.

Second, OVRs can streamline the curation process itself, making it feasible to graphically organize and mechanically monitor the availability of new resources as they emerge. We employ complementary technologies to implement this approach: web feeds in the form of RSS (Really Simple Syndication) and social bookmarking. RSS links and displays Internet sites in a unified interface. Our chosen application, Protopage, provides a visual map of the OVR landscape that updates automatically as creators upload new videos or as new repositories are discovered and linked with the feed. This creates, in effect, a living archive that serves ongoing curation efforts. The RSS and social bookmarking framework also facilitates the discovery of interdisciplinary connections that can enrich sociology curriculum. By systematically monitoring repositories from related disciplines, instructors can identify emerging hybrid fields, innovative methodological approaches, and cross-disciplinary applications of sociological concepts that might not be immediately apparent through traditional academic channels. Likewise basic to archiving is social bookmarking, which enables users to tag, save, and retrieve OVRs, individual videos, and related resources for future reference. Importantly, the tagging function of social bookmarking can be used as a device for the shorthand curation of materials.

Video Curation in Sociology

Video creation and video curation represent distinct yet interconnected practices in educational contexts. Creation transforms ideas into visual narratives through scripting, filming, and editing, employing specialized tools and storytelling techniques to convey specific messages. Curation, by contrast, involves the thoughtful selection, organization, and evaluation of existing videos to meet audience needs, with curators serving as knowledgeable guides who highlight features and relevance. While creators occasionally curate materials for reference, and instructors regularly assemble media for teaching, comprehensive curation encompasses content description, assessment of production quality, evaluation of pedagogical value, and alignment with specific educational objectives. As video content rapidly proliferates, the curator's role in making informed, targeted recommendations has become increasingly vital to educational practice.

[NOTES: discuss broad types of video curation in terms of specific curators (see location) and reference back to RSS page. increasingly curators are engaging in videographic criticism... see McIntosh and Jake Bishop and Brian Brutlag and Alexander Avila...]

Given that our primary objective here is to introduce a curation framework, we largely focus on locating, organizing, and displaying OVRs. Rather than engaging in content criticism, the discovery and accessibility of repositories is prioritized over video assessment, which would be impractical given the expanding volume of emerging online materials. Our approach identifies relevant content clusters, though we do highlight OVRs that demonstrate particular value as instructional resources. This selection provides entry points for interested instructors, who can then conduct more detailed assessments based on specific teaching objectives.

[NOTES: There is virtually nothing in the sociological literature that addresses the value of video curation, and little more that examines the utility of curation in any form...]

The scholarship on teaching with video in sociology has appeared mainly in the American Sociological Association's journal dedicated to instruction, Teaching Sociology (TS), and through a limited number of instructor-created websites and blogs. TS has consistently published research on video's pedagogical value, particularly emphasizing its role in developing sociological thinking among students new to the discipline (Belet 2017, Besek and Pandey 2022, Dowd 1999, Hoffman 2006, Prendergast 1986). The journal has examined video applications across the curriculum, from introductory sociology courses (Belet 2017, Smith 1973) to advanced topics including social theory (Fails 1988, Pelton 2013), research methods (Leblanc 1998, Tan and Ko 2004), and race relations (Khanna and Harris 2014, Stout, Earnhart, and Nagi 2020). In 2011, TS formalized its commitment to video resources by establishing a film review section, recently expanding coverage to include documentaries from commercial streaming platforms (Brutlag 2021, Lyu 2022, Smith, Smith, and Kozimor 2024).

Teaching Sociology has well-documented pedagogical approaches using traditional film, yet has been virtually silent about OVRs. In fact, the journal's engagement has been limited to just two articles--and both of these have only centered on curation: Caldeira and Ferrante's review of The Sociological Cinema (2012) and an analysis by Andrist, Chepp, Dean, and Miller 2014) examining how videos curated on that website could effectively support specific teaching goals. In our opinion, this reluctance to explore OVRs as a serious instructional resource represents an oversight in the journal's approach to contemporary knowledge dissemination.

Meanwhile, a rapidly expanding body of online video collections with explicit sociological themes has emerged. Some have even attracted substantial followings. Pop Culture Detective has garnered over one million YouTube subscribers through its incisive gender analyses of popular media, while SOC 119—Sam Richards' innovative Penn State race relations course—currently reaches more than 380,000 subscribers on YouTube. Failure to address such OVRs in the literature means that instructors are missing opportunities to connect students with accessible analyses already engaging mass audiences outside traditional academic channels.

To date, systematic curation of online video has been embodied in two websites: The Sociological Cinema (TSC) and Popular Sociology. The former initiated the curation of found video for the discipline when University of Maryland graduate-student instructors Lester Andrist, Valerie Chepp, and Paul Dean launched it in 2010. TSC developed a collaborative model where guest contributors shared not only links to videos but also specific teaching applications for given pieces of video content. What distinguished TSC from mere content aggregation, however, was its emphasis on interpretive analysis. Faculty and students were encouraged to submit critiques of each clip, contextualizing media content within theoretical frameworks and identifying significant themes that might otherwise remain unrecognized. This approach transformed video clips from illustrative examples into objects of critical inquiry, enabling instructors to model sophisticated sociological reasoning while fostering student media literacy. TSC was also unique in highlighting the pedagogical utility of brief video segments, demonstrating how concise media could be effectively integrated into lessons without consuming significant class time. This innovation preceded the rise of short-form video platforms like TikTok and YouTube Shorts, positioning TSC at the forefront of both educational methodology and emerging media consumption patterns. The site's multifaceted contribution was recognized through the 2012 MERLOT Sociology Award and favorable reviews in various publications (Caldeira & Ferrante 2012...). While its growth has slowed since 2016, TSC remains valuable with over 600 curated pieces, including multimedia modules organized around core sociological concepts.

Currently, Popular Sociology, established in 2017 by Widener University sociologist Matt Reid, represents the primary active instructor-focused curation site. Much like TSC, Reid employs a collaborative-contribution model that combines curation with critical analysis, organizing over 250 user-submitted videos into thematic collections aligned with standard course topics while providing contextual guidance for classroom integration..

Several institutional and individual initiatives have likewise contributed to video curation within the discipline, though with limited scope and systematization. The ASA's Teaching Resources And Innovations Library for Sociology (TRAILS) incorporates select teaching-with-video materials within its broader paywalled collection, providing institutional validation yet restricted access. Individual sociology instructors also have developed curation practices through blogs. For example, in the Sociology Source, Nathan Palmer initiated guidance for video integration as early as 2010, offering pedagogical strategies and classroom activities built around specific video clips rather than just collecting links. Chris Livesey's ShortCutstvBlog has evolved beyond simple video reviews to provide thematic categorization of videos across the sociological curriculum, recently featuring analytical comparisons between traditional educational content and emerging creators like the Helpful Professor OVR (Livesey 2024). Michael Miller's Sounequal blog provided a collaborative digital space where students participated over several years in the curation process, identifying and posting online videos that illustrated key concepts in social stratification—thus making them partners in building a resource library tailored to course themes. Finally, Jessie Daniels has long-advocated employing documentaries as visual texts rather than as mere course supplements (2012). Her documentary wiki, Sociology Through Documentary Film, enables collaborative curation, where instructors can contribute film recommendations and share pedagogical applications—positioning documentary analysis as an essential tool for developing critical thinking and visual literacy skills.

[NOTE: Finally, occasionally an article appears touting "the best" sociology documentaries, video producing sites, or videos... Dmello 2021 is one such example: https://www.sociologygroup.com/sociological-documentaries/ P Bowden 2024 https://www.classcentral.com/report/best-sociology-courses/#penn Prajapati 2025 https://ibusinessmotivation.com/sociology-youtube-channels/]

[NOTE: While such efforts have enhanced resource discovery, the discipline has yet to develop a comprehensive, systematically organized repository that would fully tap the pedagogical potential of online video content—a gap our proposed framework aims to address.]

Media Curation/Creation Workflow System

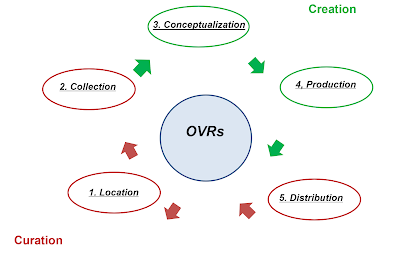

The curation framework employed in this paper is derived from a model earlier developed by the first author (see Miller 2011) which specified how instructors and students can use digital tools to engage with online learning content (videos, podcasts, photo slideshows, interactive graphics). It presents an iterative, cyclical information-processing system comprised of five components. Various digital affordances, including AI applications, can be easily integrated into each component to enhance processing efficiency.

Figure 1. Media Workflow System

Figure 1 and ensuing text describe the nature of each component and its sequence in the workflow. Outlined in red are those devoted to curation (location, distribution), and the other two in green involve creation (conceptualization and production).

1. Location relates to techniques and applications that help to find relevant multimedia content on the Web. In addition to becoming familiar with those websites with the best work, other vehicles are search and discovery engines, newsletters, alerts, and directories. RSS web feeds are particularly useful for staying abreast of emerging online content.

2. Collection relates to the function of recording and cataloging multimedia in order to retrieve for later use. Social bookmarking provides the most efficient mode for managing a large body of online media. Some services can also assist in locating quality materials by drawing on media shared among others participating within the bookmarking community. Devising useful tags for content description and evaluation is critical for curation purposes within a social bookmarking system.

3. Conceptualization involves ideas and operations that detail how multimedia will be created and employed for learning. It includes design, substantive content, and pedagogical objectives, and can be facilitated by various applications that stimulate thinking about building and using multimedia in the classroom.

4. Production entails the applications and techniques for making and/or repurposing multimedia. Production is no longer limited to those with specialized skills and access to costly equipment and software. Production now can be accomplished with such online tools as presentation makers, media editors, cartoon and data visualization creators, and most recently, AI videomaking applications.

5. Distribution makes content available for instructional purposes by placing materials online. It encompasses websites from which we can access resources, as well as various user-sharing sites and applications that allow us to easily put content online, including course management systems.

Distribution: Online Video Repositories and RSS

Distribution serves dual functions in the workflow system: it makes existing materials available to users across the Internet and enables creators to share their own content with global audiences. For our purposes, distribution encompasses the full spectrum of video-relevant websites, blogs, and channels.

YouTube stands as an essential resource, despite common criticisms. As the world's largest video-sharing platform, it offers not only an extensive array of educational channels but also various content organization features to be explored in the next section. Perhaps most significantly, YouTube widens content accessibility by allowing anyone to upload and distribute video at no cost.

Distribution also includes curator-created sites that organize existing web content, such as our specialized RSS pages. Developed with Protopage, they facilitate efficient OVR browsing and viewing through topic-based organization.

Navigating the RSS System

We invite readers to visit RSSMiller&CohenMiller2025 to see how web feeds can transform scattered online content into an organized, accessible collection. The following walkthrough illustrates how this platform can enhance content discovery and integration.

1. Explore the Main Repository

Begin by clicking the tab labeled "Sociology OVRs" to access sociology-specific repositories. This page displays over 150 OVRs arranged in three alphabetically ordered columns, providing an immediate visual overview. Scrolling through these columns reveals the diversity of sociological video content available online, from course lectures and screencasts to public sociology initiatives.

2. Locate Specific Content Providers

Alphabetical column organization enables quick location of specific repositories. For example, scrolling to the middle column, lower section reveals Jonathan McIntosh's popular Pop Culture Detective Agency mentioned earlier. Notice that this collection has two entries--the first is his website and just below that is his YouTube channel. This tandem display structure balances comprehensive coverage with navigational efficiency, ensuring that additional learning content on the website remains accessible.

3. Engage with Individual Repositories

Each content provider appears as a widget displaying its 20 most recent video uploads. Using the SOC 119 video channel by Sam Richards as an example (middle column, lower section):

a. browse video titles in the widget by vertically moving scroller.

b. hover over any title to see recency of upload (note SOC 119's high frequency of new content).

c. click on any video title to begin immediate streaming without leaving the page.

d. click on the widget's header to visit the full repository for comprehensive exploration.

4. Discover Thematic Content

The tab system organizes repositories by various topics. Clicking the "Social Stratification" tab, for instance, filters the display to show selected OVRs relevant to economic, status, and political inequality. Such organization allows instructors to quickly identify resources aligned with specific course or research interests, transforming content discovery from random browsing to targeted exploration.

5. Access Playlists

Beyond individual repositories, our collection includes playlists organized by topic. Located in the final widget of the last column on the "Sociology OVR" page, these playlists offer thematically coherent viewing sequences drawn from multiple sources. Such cross-repository curation adds significant pedagogical value by assembling complementary resources that might otherwise remain disconnected.

Practical Application Example

To illustrate the practical utility of this system, consider instructors preparing for a module on sexism. By clicking the "Gender" tab [perhaps add this tab in RSS], they would immediately access subject-relevant repositories from other instructors, scholars, journalists, influencers, activists, etc. The interface displays each source's most recent uploads, allowing instructors to identify timely or cutting-edge video content.

If instructors discover usable content from a specific creator, they might click that widget's header to explore the entire repository. Alternatively, they might notice that multiple repositories are addressing a shared theme—say gender bias in media—and incorporate these complementary perspectives into their teaching plan.

Customizing Personal RSS Pages

We encourage readers to create their own RSS pages using Protopage or a similar application. This process might begin by identifying repositories aligned with specific teaching or research interests—perhaps starting with the sociology-centered OVRs cataloged in our collection, then expanding to specialized topics or related disciplines. Protopage's intuitive interface allows users to organize widgets into personalized tabs reflecting their unique teaching portfolio. For example, an environmental sociologist might create tabs for "Climate Justice," "Environmental Movements," and "Ecological Theory," populating each with relevant OVRs. This customization shifts content discovery from time-consuming search to an automated system continuously delivering relevant resources.

In general terms, Protopage can significantly transform how instructors interact with content, be it text, video, or audio-based. Its major advantage is a distinctive graphical interface that cleanly displays uploads across multiple sites, creating what is effectively a living map of their educational media resources.

Location: Search, Aggregators, Newsletters, Online Video Repositories, RSS

Instructors often discover film materials for their classes through informal means, such as casual Internet surfing or recommendations from colleagues and students. When wanting to find videos to meet specific pedagogical needs, most turn to search engines, particularly Google and YouTube.

YouTube has several features that facilitate location. The platform's notification system alerts subscribers to new content, while its recommendation algorithm generates suggested content lists—often surfacing higher-quality videos than initially selected (note problems with algorithm). Creators can organize their materials into "playlists," subcategories of similar content that can improve repository coherence and navigation. Through "featured channels" lists, creators can build networked learning communities by showcasing complementary content. Premium YouTube subscribers also gain access to AI-powered video interrogation through the "Ask" function. Moreover, many mainstream media outlets maintain YouTube channels parallel to their paywalled sites, recognizing the platform's educational and promotional value. The New York Times exemplifies this approach, offering free access to news footage, opinion pieces, and documentaries through its massive YouTube presence.

While commercial streaming platforms have become popular sources of film consumption for television viewers throughout our society, instructors should become familiar with other, more accessible, resources at their disposal. For one, academic libraries often subscribe to extensive digital film collections. Services such as Alexander Street, with its disciplinary-focused collections across the social sciences; Kanopy, offering thousands of critically-acclaimed documentaries and independent movies; and Films On Demand, featuring curriculum-aligned educational content, represent valuable yet often underused resources. Instructors should likewise become familiar with freely available online repositories of both short-form and feature-length, such as those we have catalogued on our RSS pages, "OVR Documentaries" and "OVR Movies." The OVRs listed here impose no barriers to use, and some also feature perspectives and formats not typically represented in commercially streamed media. For example, both Aeon and Omeleto specialize in collecting emotionally resonant short movies, making them particularly compelling for instructors seeking to arouse empathy in the classroom.

Beyond YouTube, several alternative platforms also merit exploration. Vimeo attracts professional creators and often hosts higher production value content, while DailyMotion specializes in short-form videos and user-generated content. Generic internet curation sites can further enhance OVR discovery. Video aggregators like Digg and Pocket collect and categorize content from across the web, often highlighting educational materials that might otherwise go unnoticed.

Media-focused websites and blogs serve as valuable locators of educational content. Open Culture stands out for its comprehensive collection of free educational media and daily distribution of excellent curated multimedia, whereas Diggit Magazine regularly features scholarly video analyses. Newsletter subscriptions can streamline discovery—weekly announcements from The Deep Dive highlight emerging content of quality, while the Retro Report newsletter often provides supplementary teaching materials alongside video recommendations. Award-recognition platforms like Peabody Matters and The Webby Awards offer access to critically-acclaimed educational content, often accompanied by expert commentary and teaching resources.

Nevertheless, in our opinion, RSS offers the most efficient approach to content discovery. By automatically aggregating new uploads from selected providers, RSS eliminates the need for manual checking of multiple sources. Curators typically integrate the most pedagogically relevant OVRs into their RSS feeds, creating a pipeline of quality educational content. This automation allows instructors to become aware of new materials while minimizing the time invested in content discovery. We should point out, however, that a notable limitation of Protopage is its lack of active user notifications for new content uploads, therefore requiring us to employ complementary notification systems through YouTube and Feedly.

Collection: Social Bookmarking

Collection in our workflow serves the essential function of recording media resources for future retrieval. While this process involves bookmarking, the technology employed significantly affects curation effectiveness. Device-specific or browser-based bookmarking tools (such as those native to Chrome or Firefox) offer limited functionality for curation practices. Instead, cloud-based social bookmarking platforms provide the best solution for managing extensive video collections.

Social bookmarking systems not only facilitate organization of digital resources across multiple devices but also may generate collective intelligence through community participation. For instance, our social bookmarking service of choice, Pinboard, enables users to discover additional content through the shared resources of other community members. This application thus serves both collection and location functions within the workflow.

Effective social bookmarking hinges on developing a meaningful tagging taxonomy. Tags serve multiple purposes within the curation process: they enable content description, facilitate thematic organization, support assessment, and enhance retrievability. A well-designed tagging system transforms a simple collection into a curated archive by adding layers of meaning and context to each resource.

Given our interest in online film resources, several types of descriptive designations are fundamental. Scope of resource tags distinguish between comprehensive video collections (OVRs), thematic subcollections within OVRs (playlists), individual pieces (videos), and segments of pieces (clips). Type of video tags specify... Origin tags identify whether content is original (produced for the OVR), found (appropriated from elsewhere online), or remixed (incorporating found video into new compositions). Accessibility tags indicate if content is restricted through institutional controls or paywalls. Of course, discipline, subfield, and concept tags importantly differentiate content by subject matter.

Quantitative metrics can further enhance collection organization. Tags indicating repository size (e.g., small: <50 videos, medium: 50-200 videos, large: >200 videos) and audience reach (e.g., subscriber count in thousands) provide valuable context for assessing an OVR's significance and potential classroom utility. These metrics, combined with careful qualitative tagging, create a comprehensive system for evaluating and retrieving video resources aligned with specific pedagogical needs.

For purposes of this paper, we have created an extensive Pinboard collection that illustrates how systematic tagging can transform scattered video resources into a structured, retrievable archive. To explore this collection and understand its organization, readers can access our public bookmarks at https://pinboard.in/u:michaelvmiller. The following walkthrough demonstrates how this collection can be navigated and utilized for educational purposes.

Navigate the Collection

1. Basic Search and Filtering

Begin by examining the tag cloud on the right sidebar, which visually represents our taxonomy. The size of each tag indicates its frequency of use. Clicking on the tag "OVR" (or typing it in the search box) will display all bookmarked Online Video Repositories, providing a comprehensive view of available content sources. This simple filter immediately transforms a collection of thousands of bookmarks into a focused subset of repositories.

2. Combine Tags for Precision

The true power of social bookmarking emerges when combining multiple tags. Unfortunately, our publicly shared Pinboard page allows only for one tag to be used at a time. Therefore, watch this brief video to see how multiple tags assist in the retrieval process. As shown, selecting both "power" and "3013" tags along with "video" narrows results to videos specifically addressing political inequality within the context of social stratification. Adding the tag "gem" or "excellent" further refines results to show only those deemed to be of high quality—ideal for instructors planning comprehensive course units on social stratification.

3. Discover Interdisciplinary Connections

Our collection includes OVRs from disciplines adjacent to sociology, tagged appropriately. For example, selecting "ANT" (Anthropology), "ECO" (Economics), or "SSC" (Social Science) reveals□ repositories that bridge multiple fields. This capability is particularly valuable for teaching topics that benefit from cross-disciplinary perspectives, such as social stratification.

4. Evaluate Repository Quality

We have implemented evaluative tags to indicate repository quality and potential classroom utility. Filtering for quality and "classroom:ready" [NOTE: check on bundling] identifies repositories that require minimal instructor preparation before classroom integration. Conversely, repositories tagged "classroom:needs_context" signal content that requires additional framing or discussion to maximize pedagogical value.

5. Find Specialized Content Types

Content format tags help instructors locate specific video types. For example, "format:documentary" identifies repositories specializing in longer-form analytical content, while "format:commentary" reveals channels featuring expert analysis of contemporary issues. For instructors seeking concise content for in-class use, "format:short" identifies repositories with videos under ten minutes in length.

6. Accessibility Considerations

Tags like "access:paywall" and "access:restricted" help instructors quickly determine if the content is not open access (freely available film is the unlabeled default). This information is crucial when planning assignments that require student engagement outside class hours.

Practical Application Example

To illustrate the practical utility of this system, consider an instructor preparing materials for an introductory sociology unit on racial stratification. By selecting tags "sociology," "race," "classroom:ready," and "access:open," they would immediately access a filtered collection of high-quality, freely available video repositories addressing racial inequality from a sociological perspective. The search results might include Sam Richards' SOC 119 channel alongside smaller repositories from academic institutions and non-profit organizations, each offering unique perspectives and teaching opportunities.

The instructor could further refine results by adding the tag "format:discussion" to find content that models productive classroom conversations about race, or "format:data_visualization" to locate resources that present statistical information on racial disparities in compelling visual formats. Each resource's description and tag set provides context for potential classroom applications, allowing for informed selection based on specific teaching objectives.

Build Personal Collections

We encourage readers to develop their own social bookmarking practices using either Pinboard or another application, such as Diigo. Beginning with a small collection focused on a single course or topic allows for experimentation with tagging strategies without overwhelming initial curation efforts. As comfort with the system grows, collections can expand to encompass broader teaching areas, eventually developing into comprehensive personal archives of online resources.

For instructors new to social bookmarking, we recommend starting with three basic tag categories: subject matter, content type, and potential course application. Even this simple taxonomy significantly enhances retrievability compared to standard bookmarking approaches. Over time, tags can be refined and expanded to create increasingly sophisticated taxonomies tailored to individual teaching needs.

Pinboard offers a subscription-based service for an annual fee of $22 that provides comprehensive functionality for serious curators (a brief tutorial is available here). This investment delivers significant value through its streamlined interface and archiving and community search features. While several free alternatives are available, we have found that subscription-based applications tend to have greater longevity and stability. Their business model creates financial incentives for continued maintenance and development, unlike some free services that have disappeared when creators lost interest or funding.

Integrated Media Curation: Merging RSS and Social Bookmarking

Combining RSS feeds and social bookmarking improves both the discovery and organization of online video as curators can develop a more complete and efficient workflow that exploits the strengths of each system. RSS excels at real-time content discovery and automated updates, and with Protopage, provides a graphic view of the current OVR landscape. Social bookmarking, meanwhile, offers superior organization, evaluation, and retrieval capabilities for long-term collection management. When integrated, these systems create a continuous curation flow: RSS serves as the front-end, continuously surfacing new content from selected OVRs through its automated feed system, and social bookmarking functions as an essential back-end, providing structured, retrievable archives of content deemed worthy of saving, identified through RSS exploration.

Integrating the two might follow this process:

1. Configure RSS to monitor selected OVRs. Use Protopage to create a visual dashboard of relevant repositories organized by discipline and teaching interests.

2. Establish a social bookmarking workflow. Develop a tagging taxonomy in Pinboard that accommodates both description and evaluation.

3. Create a bridging mechanism. Develop a procedure for transferring content discovered via RSS into the social bookmarking system. For example, when instructors discover potentially useful video through their RSS dashboard, they would: (a) evaluate its quality and relevance, (b) bookmark in Pinboard with appropriate tags, and (c) add any contextual notes about possible classroom use.

[NOTE: Provide screencast video illustrating the bridge.]

Emerging Benefits from Integration

Several benefits emerge from the synthesis that neither system provides independently:

1. Temporal Depth with Evaluative Context

Integration creates a curation system with both temporal dimensions (RSS showing new video, social bookmarking preserving valuable video) and evaluative dimensions (RSS tracking quantity, social bookmarking specifying quality). This allows curators to maintain awareness of content evolution, while building a curated collection of usable resources.

2. Cross-Pollination of Discovery Methods

Used together, these systems enable cross-referential discovery that would not be possible in either system alone:

(a) Using RSS to identify active video creators within a field, then searching for their content in the social bookmarking community.

(b) Discovering thematic patterns in social bookmarks that suggest new RSS feeds to follow.

(c) Identifying complementary resources across repositories that might be tagged together in social bookmarking.

3. Collaborative Curation Networks

The social dimension of bookmarking combined with the currency of RSS creates opportunities for collaborative curation networks where educators:

(a) Share curated RSS configurations with colleagues.

(b) Build collective social bookmarking repositories with specialized taxonomies.

(c) Develop shared evaluative criteria for content assessment